Audit committees, management, investors, regulators, and external auditors expect your business process controls to be effective, efficient, and testable. See how to extend your GRC functionality to identify control exceptions in your SAP system by locating data in SAP tables and running forensic audit queries.

Out of the box, compliance solutions such as the SAP GRC technology foundation may not meet all of your unique business process control objectives. With an understanding of configuration settings, account mappings, security authorizations, and data structures, you can customize your system and extend your system controls to meet your specific business needs.

I’ll show you how to design forensic audit queries that identify control irregularities and detect fraud in the purchase-to-pay (P2P) process. Identifying the tables that store P2P data and understanding how certain fields affect the control environment allows you to design and implement effective and efficient forensic audit queries. Working with experienced IT personnel can help you understand which fields affect your control environment.

Deciding which transaction and master data fields are important to your control environment depends largely on your particular implementation and risk appetite. I currently use about 950 forensic audit queries across the SAP enterprise to help isolate master data control deficiencies; identify unauthorized or improper changes to transactions and master data; reconcile and age GR/IR accounts; confirm SAP calculation routines, such as depreciations; uncover fraudulent activity; control circumvention schemes; and isolate actual segregation of duty violations.

I’ll show you how to enhance your GRC implementation by extending its functionality to help monitor and detect control exceptions. I’ll explain how you can locate master and transactional data in SAP tables and then how to download this data to Microsoft Access, where you can design and develop forensic audit queries to help monitor for control deficiencies. First, I’ll go over the way some data in the SAP system is structured, which requires you to use forensic audit queries.

Your SAP system consists of interrelated configuration settings, programs, transactions, variants, and reports supported by a complex data structure. As SAP introduces new functionality, the system continues to increase in complexity and, by extension, auditability. Table 1 lists some metrics in R/3 3.1, R/3 4.5, and SAP ERP Central Component (ECC) 6.0. Note that these are approximations and may not match your version exactly.

| Transparent tables (table DD02V) |

9,648 |

33,553 |

66,841 |

| Transaction codes (table TSTCT) |

12,947 |

52,308 |

80,262 |

| Security objects (table TOBJ) |

487 |

1,384 |

1,946 |

|

| Table 1 |

Metrics in different SAP systems |

The situation can become more complex when your system stores the same data element in multiple tables. For example, the SAP system uses the vendor payment term (data element ZTERM) to determine when a check should be issued to a vendor after a valid invoice has been entered into the system. Data element ZTERM is stored in multiple tables as shown in Table 2.

| LFB1 |

Vendor master — company code |

| LFM1 |

Vendor master — purchasing organization |

| EKKO |

Purchase order (PO) header |

|

| Table 2 |

Tables that contain vendor payment terms |

Information is commonly stored in multiple places with master or configuration data, which is usually subject to intense controls and monitoring. Unless the configuration is modified, you can modify data coming from master data and configuration tables at several points in the P2P business process, adversely affecting the control environment.

This de-normalization of master and configuration data presents many audit and control challenges when implementing a GRC strategy. For example, monitoring payment term differences between master data and purchase orders may help achieve operational control objectives affecting cash flow, vendor performance, and purchasing group performance. Monitoring payment term differences between master data and vendor invoices, however, may help achieve financial reporting control objectives. That is because the timing of payments to vendors can affect several financial statement assertions, including existence/occurrence, rights/obligations, or allocation.

As with any project, a sound approach helps you develop sound forensic audit queries and achieve success. I advise my clients to follow an approach similar to the one below:

- Step 1. Map out your business process

- Step 2. Document your control (or GRC) objectives

- Step 3. Identify risk points in the business process

- Step 4. Document each significant class of transaction (SCOT), such as master data, PO, receiving, and invoicing

- Step 5. Locate the SAP transaction code facilitating the SCOT (e.g., XK03 or XK01)

- Step 6. Identify fields in each transaction code that relate to the GRC objective

- Step 7. Locate technical table and field names

- Step 8. Download pertinent data

- Step 9. Load into a data query tool

- Step 10. Design forensic audit queries

The first five steps should already be included in your control documentation, especially if you are subject to Sarbanes-Oxley section 404. Therefore, I’ll assume you’ve completed steps 1–5 and will not discuss how to achieve them. Using the vendor payment term data element mentioned above, I’ll show you how to perform steps 6, 7, and 8. I will not demonstrate step 9 because the procedure required to load data is dependent on the query tool chosen. (I use Access in all my examples.) In step 10, I’ll show several examples demonstrating how you can use Access to design and test effective forensic audit queries prior to implementation.

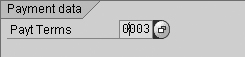

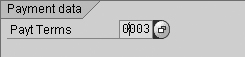

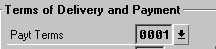

Step 6. Identify fields in each transaction code that relate to the GRC objective. If a control objective is to ensure that all vendor payment terms are valid and authorized, you would find that master data personnel maintain this field using transactions XK01, XK02, FK01, or FK02 in step 5. Using transaction XK03 (display vendor master), go to the Payment Transactions Accounting tab where the system displays the vendor terms associated with the company code (Figure 1). You can also maintain these vendor payment terms on the Purchasing Org Data tab, which can be different (Figure 2).

Figure 1

Payment terms — company code

Figure 2

Payment terms — purchasing organization

When speaking to purchasing personnel, you also find that you can maintain the vendor payment terms on the purchase order using transactions ME21 or ME22. Using transaction ME23 (purchase order display), you find the vendor payment terms on the PO header screen (Figure 3). In the next step, you locate the technical table and field names for each of these data elements.

Figure 3

Payment terms — PO header

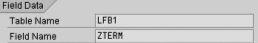

Step 7. Locate technical table and field names. As I mentioned above, ECC 6.0 has thousands of tables and each table has several fields that can overwhelm experienced SAP IT personnel. Fortunately, SAP provides a way to help identify the technical names of tables and fields. To identify the technical table and field name for the vendor payment term company code and purchasing organization (Figure 1), perform the following actions:

- Go to transaction XK03 to view a vendor

- Place the cursor on the field

- Press F1 (help)

- Click on the tools icon to display technical information (Figures 4 and 5)

Figure 4

Payment terms — company code

Figure 5

Payment terms — purchasing organization

To identify the technical table and field names for the vendor payment term on a purchase order (Figure 3), perform the following actions:

- Go to transaction ME23 and enter a PO number

- Go to the PO header screen and place the cursor on the vendor payment term (Figure 3)

- Press F1 (help)

- Click on the tools icon to display technical information (Figure 6)

Figure 6

Payment terms — PO header

As you can see in Figures 4, 5, and 6, the vendor payment term is located in three different tables (LFB1, LFM1, and EKKO). From a risk and compliance standpoint, this presents several challenges because the vendor payment term can be different in all three tables. You can modify configuration to help ensure integrity, but in my experience, the required configuration changes are hardly ever implemented.

Step 8. Download pertinent data. Using the technical table name identified in the previous step, perform the following steps to download data:

1. Go to transaction SE16 (data browser)

2. Enter the table name (e.g., LFB1), and press Enter (Figure 7)

Figure 7

Transaction SE16 (data browser initial screen)

3. After the field selection screen is displayed (Figure 8), press F8 (execute) or click on the execute icon to bring up the table records

Figure 8

Transaction SE16 (field selection screen)

After executing the transaction, the SAP system retrieves the records from the database and displays them on the next screen. To download the data, press Shift and F8 at the same time to bring up the screen shown in Figure 9. This allows you to select the directory and name the file that you are downloading. I use the table name as the file name and always use a .txt extension. Also, the downloaded file is tab delimited, so you can easily import it into several desktop applications, including Microsoft Excel or Access.

Figure 9

Transaction SE16 (download file name)

Downloading data can be challenging for various reasons. For example, you may want data from some tables that are so large that the SAP system cannot retrieve all of the records you want due to technical limitations configured by the Basis team. This article will not attempt to explain all the functionality of transaction SE16 to retrieve data. If you need help getting data, your IT personnel can provide assistance with extracting data from your SAP system. The key here is that you need to know what data you want and where it is stored in the system.

Step 9. Load into a data query tool. You can use several desktop query tools to load your data. I use Access to design forensic audit queries because it allows me to adapt and refine queries to meet specific requirements prior to production. Because you have so many options to choose from, I will not demonstrate how to load data into any specific tool. If you are not familiar with desktop query tools, I suggest you work with your IT department to identify and select a tool that meets your requirements and IT standards.

Step 10. Design forensic audit queries. After you download the data and import it into a data query tool, you can begin designing forensic audit queries that meet your control objectives. In the examples below, I use some common control objectives and demonstrate how you can use forensic audit queries to test the effectiveness of configuration and security settings designed to help achieve the objectives.

At many companies I work with, the vendor payment terms are tightly controlled and monitored by a small group of employees in the vendor master data group in accounting. There are several business reasons for controlling the payment term on which a company pays vendors. For example, this data element can affect operating cash flow, result in improper kickbacks, and affect loan covenants tied to the financial statements.

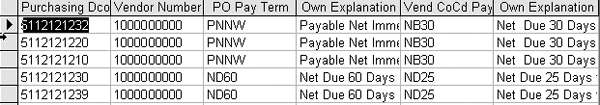

In most cases, the payment term should be the same on tables LFB1 and LFM1. In turn, when purchasing creates a PO, the SAP system assigns the vendor payment per LFM1 to the PO. Regardless of the technicalities of how a PO is assigned a payment term, you want to make sure all POs have the same payment term per the company code (i.e., LFB1) because the control objective states that all POs should carry the payment term assigned at the company code level. In Access, design a forensic audit query to join tables EKKO and LFB1 (Figure 10).

Figure 10

Join EKKO and LFB1

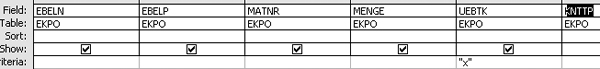

I included tables T052 and T052_1 so I can display the vendor payment term and PO payment term, respectively. Next I selected the fields shown in Figure 11 for the query.

Figure 11

Fields selected for forensic audit query

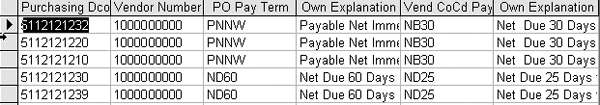

Notice that I entered <>[lfb1].[zterm] in the criteria selection for the ekko.zterm field. This criterion displays only those records in which the PO payment term does not equal the payment term per the vendor master file at the company code level. When you execute this query in Access, you get the results shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12

Forensic audit query results

In this example, vendor 1000000000 has a vendor payment term of PNNW, which tells the system to pay a valid vendor invoice immediately. The payment terms per the vendor master record at the company code level are NB30, which stands for pay invoice net 30 days after the invoice is received. Discrepancies like the ones noted above require follow up, but the query result gives you a headstart on shoring up a key control objective.

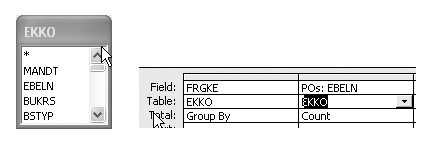

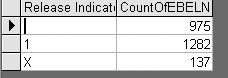

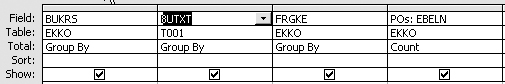

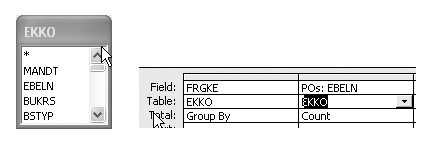

Many of my clients require that POs be released (i.e., approved) to help ensure that purchasing practices and standards are met. In the SAP system, the FRGKE field on the PO header table EKKO tells the system whether a PO requires release. If this field is blank, the PO does not require release. Using table EKKO, design a summary forensic audit query in Access to count the number of POs by release status (Figure 13).

Figure 13

Summary forensic audit query for identifying POs that do not require release

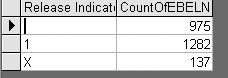

In Figure 14, the summary forensic audit query results show that a lot of POs did not require a PO release because the release indicator field is blank. To understand whether this is a corporate-wide problem or an issue in one area of the company, you can modify the PO release query in Access to include the company code (i.e., BUKRS) (Figure 15).

Figure 14

PO release query result

Figure 15

Modify PO release query to include company code — table EKKO; field BUKRS

Figure 16 shows that the majority of deficiencies (i.e., POs that do not require release) are found in a new company code (2000). In this example, the PO release procedures configured in the IMG use the company code as one criterion for determining release requirements. When a new company was purchased by the organization and brought into the SAP system, the Materials Management (MM) configurator (who was not privy to the initial implementation) did not realize company code was a criterion for release and did not configure the release procedures to require release for the new company code (2000). After some quick configuration modifications, IT remediated this deficiency.

Figure 16

PO release query result with the company code

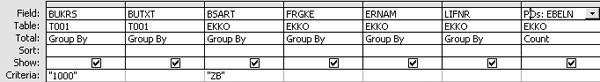

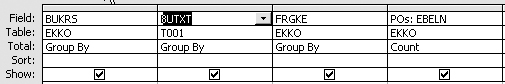

What about the other 36 in company code 1000? How did these slip through without requiring release? Upon review of the PO release procedures with classification, you notice that Purch Doc Type (PO document type) is also a criterion for release, so you limit the query to company code 1000 and add PO document type (i.e., BSART) to the Access forensic audit query (Figure 17).

Figure 17

Modify PO release query to include PO document type — table EKKO; field BSART

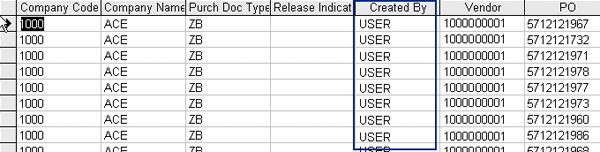

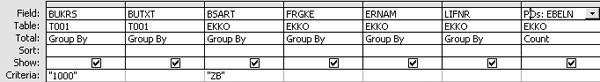

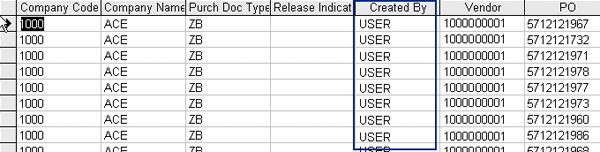

As seen in Figure 18, PO document type ZB is a custom PO document type created by the company. You then limit the query to PO document type (i.e., BSART) ZB and include the user ID (i.e., ERNAM) and vendor number (i.e., LIFNR) to see who has been issuing the PO and to whom (Figure 19). The results from executing the above query are shown in Figure 20.

Figure 18

Results from the forensic audit query in Figure 17

Figure 19

Access forensic audit query limited to PO document type

Figure 20

Results from the forensic query in Figure 19

What you realize is that the same ID in the Created By column has been issuing purchase orders to the same vendor using a PO document type that doesn’t require release. Based on follow-up meetings with a purchasing manager, PO document type ZB was migrated to production by mistake because the IT project using this document type was canceled. Upon further review, management found that the employee was exploiting a configuration weakness to bypass PO approval requirements.

The above example shows how you can use summarized forensic audit queries on the PO table EKKO and quickly find configuration deficiencies and fraudulent activity. This in turn helps you to focus your efforts on high-risk activities. You can develop summary forensic audit queries for any SAP-enabled business process. The trick is finding the right table and designing queries that allow you to see what type of transactions are taking place in your organization. Across the SAP enterprise, I use 130 summary forensic audit queries to help me achieve a top-down and risk-based approach in the purchase-to-pay, order-to-cash, finance, asset management, and HR/Payroll business cycles.

Three-way match is a common automated control in most integrated SAP environments and is relied on heavily by most external audit firms. This automated control helps to ensure the vendor invoice quantity matches the quantity received and the unit price per the vendor invoice matches the unit price per the PO. You can set other vendor invoice tolerances, but these are the most common that I’ve seen. Typically, auditors test three-way match configuration settings and usually pass them in most environments. However, Purchasing, Accounts Payable, and other personnel can employ several automated methods to bypass three-way match configurations.

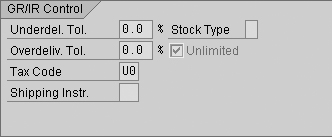

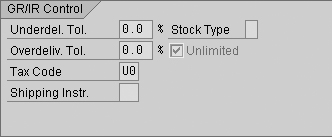

For example, if you look in the item detail for a PO, you find a check box labeled Unlimited (Figure 21). In legacy transactions (e.g., ME23), this data is classified under the heading GR/IR Control. In newer transactions (e.g., ME23N), it is listed under the heading Delivery. Regardless of the heading, the check box has the same impact on the control environment.

Figure 21

GR/IR Control per transaction ME23 — display purchase order

You can use this flag to circumvent automated configuration controls, including PO release configurations and three-way match configurations. You can set it from multiple sources, including manually by the user via transaction ME21N or ME22N (direct), through purchasing value keys located on the material master via transaction MM01 or MM02 (indirect), or by referencing an outline agreement in transaction ME31 or ME32 (indirect).

Note

This is a general discussion and other configuration and manual controls may be in place to prevent or detect circumvention.

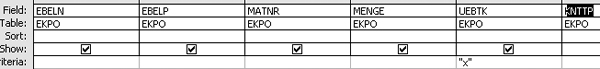

Because you performed steps 6 through 9, you know this flag is maintained in table EKPO (PO line item) and the technical field UEBTK. Designing a forensic audit query against EKPO, such as the one shown in Figure 22, helps you to identify all PO line items that have the Unlimited over delivery flag set (i.e., an X in the field). If field UEBTK has an X in it, the Unlimited over delivery flag is set for the PO line item. Executing the query in Figure 22 yields the results shown in Figure 23.

Figure 22

Forensic audit query to identify PO line item with Unlimited over delivery flag set

Figure 23

Results from Figure 22 forensic audit query

In the example in Figure 23, you can see that several POs were issued for line items that did not reference a material number (in the Material column), the order quantity is 1 (in the Order QTY column), an unlimited amount can be received (in the Unlimited Over D... column), and the account assignment is unknown (in the Acctr Assignme... column). These POs allowed purchasing personnel to circumvent PO release procedure controls because the unlimited over delivery flag has been set for the PO line item. The unknown account assignment flag helps facilitate the internal control circumvention because the receiver can post journal entries to a G/L account receiver “that works” and may not be monitored. This can dupe AP personnel into paying improper invoices for products that were not required or approved because the automated three-way match was successful.

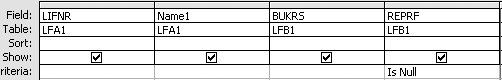

Using the SAP system to check for duplicate invoice numbers when an AP employee enters a vendor invoice into the system is another common control in most integrated environments. This automated control helps ensure that vendor invoices are not paid multiple times. Two steps ensure that this control is effective. First, you must have properly configured the SAP system using IMG transaction OMRDC (configure the duplicate invoice check). Then vendor master personnel must set the duplicate invoice flag (i.e., data element REPRF) on the vendor master record (table LFB1) using transaction XK01, FK01, XK02, or FK02. Here, I’m assuming that the system was properly configured to check for duplicate invoices.

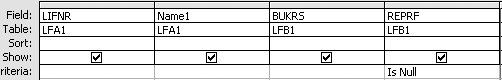

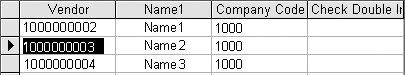

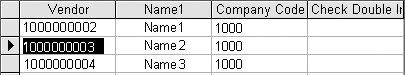

After downloading and importing the vendor master data into Access, the forensic audit query shown in Figure 24 is designed to verify if the duplicate vendor invoice flag is set for all vendors. The Is Null value in the criteria line identifies those records that do not have a value in the field REPRF (check double invoice). The query identifies several vendors that do not check for duplicate invoices, as shown in Figure 25.

Figure 24

Forensic audit query to identify the vendor master records without the duplicate invoice flag set

Figure 25

Results from Figure 24’s forensic audit query

Bryan Wilson

Bryan Wilson is president of Acumen Control ERP, which specializes in SAP risk, advisory, and forensic audit services. With more than 20 years of experience in IT risk management, he has managed SAP R/3-enabled controls design and assessment teams for both KPMG LLP and Deloitte & Touche LLP. Bryan has advised audit committees, executive teams, and audit partners at several multi-national companies of the residual risks in their SAP R/3-supported business cycles. He also helped several multi-national clients re-engineer their SAP R/3 security architecture and re-architect business processes after internal control failures or fraud were identified. He currently helps clients assess their SAP control environments using his forensic audit queries, which clients can use to enhance their own off-the-shelf audit query tools. Bryan has a B.S. degree in computer science and is a Certified Public Accountant (CPA), Certified Information System Auditor (CISA), and an active member of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners.

You may contact the author at bwilson@acutrolerp.com.

If you have comments about this article or publication, or would like to submit an article idea, please contact the editor.